15, October 2025

Do we produce too many graduates?

Consider the following statements:

- “Why today’s graduates are screwed.” Headline in the Economist in June.

- “Be a plumber” – advice from Geoffry Hinton, the godfather of AI, when asked what career advice he would give his children.

- “AI is stealing entry-level jobs from university graduates.” Headline in The Logic in June.

- “83% to 90% of workers with a bachelor’s degree or higher were in jobs that could be highly exposed to AI-related job transformation. Statistics Canada report.

- “AI more likely to transform jobs of highly educated workers” Canadian HR Reporter.

So, are we producing too many graduates?

The supply.

According to Statistics Canada, Canada ranks first among G7 countries in the for the share of working-age people (aged 25 to 64) with a college or university credential (57.5%). The number of university graduates produced has almost doubled in the last 20 years, as shown in the table below. The number of graduates produced increased by 81% since 2000, while the population only increased by 24%

| 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2015 | 2020 | |

| Bachelors | 132,600 | 162,300 | 196,700 | 203,800 | 239,200 |

| Masters | 29,200 | 35,300 | 48,700 | 62,800 | 64,000 |

| Doctorate | 4,200 | 3,500 | 6,600 | 5,700 | 6,600 |

Source: Statistics Canada 37-10-0030-01

This increase was driven by international students who now represent about 18% of graduates. International students pay about five time the tuition that Canadian students pay. About two thirds of the international student graduates leave Canada after graduating and one third become landed immigrants, according to Statistics Canada.

In the 2010s, the population of young adults aged 18 to 24 in Canada declined. However, the population of young adults is projected to experience rapid growth in the next 10 years. This demographic change may lead to increased domestic enrolment, and thus the underlying relationship between changes in enrolments of domestic and international students may shift in the next decade.

The demand.

The Canadian Occupational Projection System (COPS) projects the need for different jobs 10 years into the future. COPS latest projection was done in the spring of 2024. They point out that technological change is a main factor influencing future job growth, driven by automation and artificial intelligence.

Automation can affect employment in two opposing ways: negatively, by displacing workers from tasks they previously performed, and positively, by increasing the demand for labour in other jobs or industries. However, most experts agree that large-scale job losses are unlikely over the next 10-20 years, as automation is most likely to affect specific tasks, rather than entire occupations.

AI related job transformation can affect employment in two ways: by AI potentially replacing tasks in the future, or by complementing them. In 2021, 31% of workers in Canada were in occupations in the first category, while 29% of workers were in the second.

They concluded that over the projection period (to 2033), occupations that usually require a university degree are expected to have the strongest overall employment growth, contributing also to the largest number of jobs created among all educational levels. This is mostly the result of strong growth expectations in occupations related to professional services in health, as well as in the natural and applied sciences fields, especially among the information technology sectors.

Although their projections were made before the government’s decision to reduce immigration, they said that should not affect their report as immigrants produce both supply and demand.

What’s the balance?

The COPS projection estimates the supply and demand for different occupations out to 2033, as follows.

| Number of occupations | Share of total employment 2023. | |

| Strong risk of shortage | 38 | 11% |

| Moderate risk of shortage | 65 | 16% |

| Balance | 365 | 72% |

| Moderate risk of surplus | 11 | 0.7% |

| Strong risk of surplus | 6 | 0.2% |

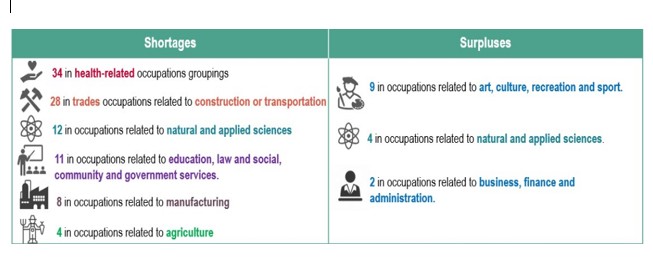

The big shortage and surplus occupations are shown below.

Source: COPS

Source: COPS

The list of shortages does include plumbers, so Geoffrey Hinton’s suggestion was on the mark.

What does Statistics Canada say about the impact of AI?

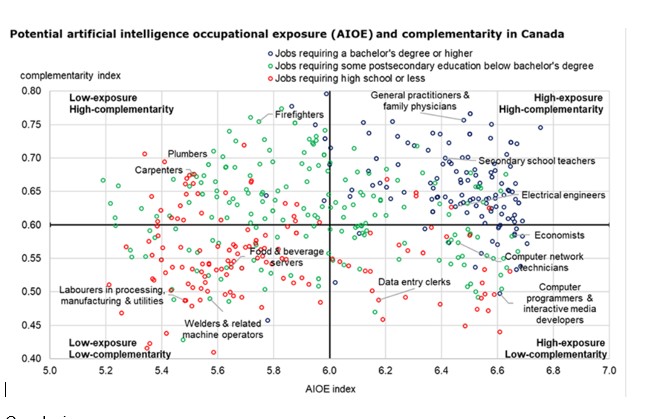

StatsCan analyzed a wide range of jobs by two factors – exposure and complementarity. By exposure they mean whether AI might impact the job, given the usual activities involved. Low complementarity means that the occupation has many tasks that may be replaced by AI. High complementarity means jobs that benefit from AI.

The matrix below shows these plotted on a two-by-two matrix. The horizontal axis is a measure of exposure to AI (low to high), the vertical axis is a measure of complementarity (low to high. Most of the jobs requiring a bachelor’s degree are clustered in the top right quadrant, which means they are highly exposed to AI and will benefit from it. Jobs on the left-hand side would not be affected much by AI. These include many manual jobs such as plumbers, carpenters, and labourers. The worst quadrant to be in is the lower right which is highly exposed to AI and has many tasks that may be replaced by AI. There are not many graduate jobs in that quadrant, but it does include economists and computer programmers.

Conclusion.

The COPS forecast shows that the great majority of occupations will be in balance or at a moderate risk of shortage by 2033, so that should not be a cause of alarm about massive job losses due to AI. However, at this point we really don’t know what the impact of artificial intelligence will be on the economy in the future. There are shortages projected in many occupations where a degree is required, so that suggests that we will need more graduates in the future than currently projected.

The StatCan analysis shows that most graduate jobs will actually benefit from AI

So it might be that the apocalyptic statements from AI experts about massive job losses are overkill. Only time will tell.

Peter Josty

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.