30, October 2025

Can ideas from the Nobel Prize help Canada’s growth problem?

The Nobel Prize in Economics in 2025 was awarded half to Joel Mokyr, and half to Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt for deepening our understanding of innovation led growth. Canada has a major growth problem – the OECD predicts that it will have the lowest growth among OECD countries in the period 2030-2060. Can some of their ideas help Canada’s growth?

Background

Mokyr is an economic historian, and it is unusual for an economic historian to be awarded the Nobel Prize. Aghion and Howitt are more mainstream economists with quantitative modelling.

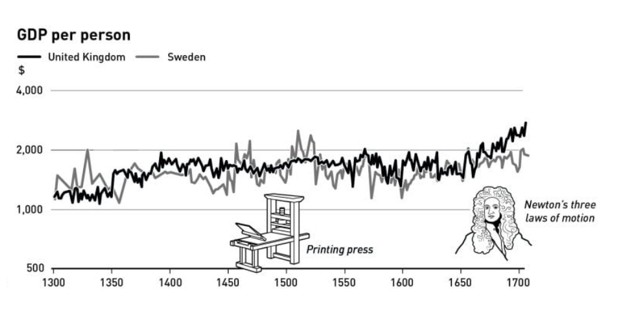

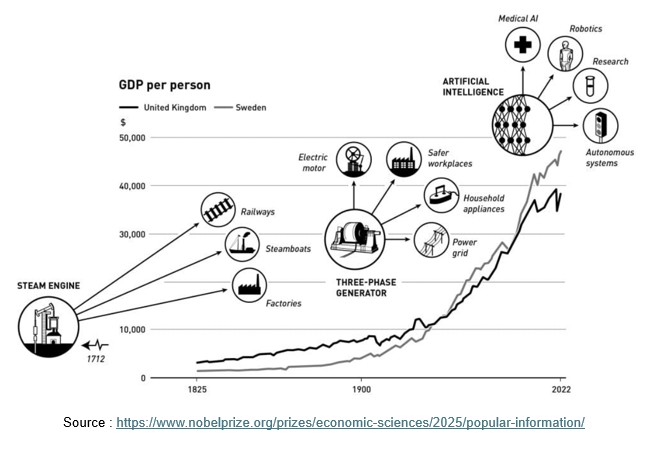

The problem they were trying to understand is why economic growth took off spectacularly around 1800, after being flat for hundreds of years, first in the UK and then more widely, and continued ever since. This is illustrated in the two diagrams below, both from the Nobel Prize web site.

Key ideas.

Mokyr’s key theme is that the growth of useful knowledge is at the heart of economic growth. He distinguishes between two types of knowledge – propositional knowledge and prescriptive knowledge. The first is knowledge about natural phenomena (e.g. the laws of aerodynamics), and the second is about how to apply that knowledge practically (e.g. designing a better airplane). Only the second kind can be patented. It is interesting that he doesn’t use terms like science and technology or practical or applied. The interplay between propositional knowledge and prescriptive knowledge is a constant theme in his work, in particular the ease and cost of access to different kinds of knowledge.

A major factor affecting this is the cultural context. One reason that the Industrial Revolution started in Britain (rather than France) was due to the Glorious Revolution in England in 1688 that reduced the arbitrary power of the king and established parliament as the main power in England. He also points out that major innovations are often developed well before the knowledge of how they work is fully established. For example, the Wright brothers were able to design a plan that flew in 1903 with empirical knowledge, well before the publication in 1918 of aerodynamic theory that showed how to design wings scientifically. Major innovations also take a long time to make an impact, and this often involves developing the underlying theory of why it actually works. For example, Faraday figured out how to make electricity from mechanical action in 1831, but it took another 50 years until the underlying theory had been developed to the point where it could be commercially useful.

Aghion and Howitt developed a mathematical model of the creative destruction process described by Joseph Schumpeter. The main point is that the economy is in a constant state of churn where incumbent firms are challenged by others who come up with a better idea, and who are in turn challenged by others. It is this constant renewal that drives economic growth.

Some lessons for Canada.

- The historical record shows that major changes in useful knowledge take a long time to have significant impact, often measured in decades. So, when we look at new technologies such as artificial intelligence, synthetic biology and quantum computing we should not expect that they will be a magic bullet to improve economic growth overnight. Their impact, despite all the hype, will likely be felt over the next several decades. Lesson: Don’t expect new technologies to impact the economy in the short term.

- Creative destruction shows that we need to encourage the up-and-coming firms who are candidates to displace today’s incumbent firms and become major players in the economy 10 or 20 years in the future. This means doing whatever we can to encourage competition and, most important, keeping new firms in Canada so they can grow here rather than elsewhere. Another lesson is that we should not artificially sustain dying industries, because that would slow economic growth. This is very difficult for elected officials as the decline of a major industry involves disruption and job loss. Lesson 1: Encourage competition and facilitate the decline of non-viable industries rather than supporting them.

Lesson 2: Encourage startups, particularly those with ambitious scalable ideas.

- Mokyr’s work shows that social and political factors often stop or even reverse the impact of new knowledge. This is a major reason that economic growth was stagnant before 1800. There seems to be quite an “anti-science” mood developing round the world today, particularly in the US, with climate change deniers, anti-vaxxers and attacks on universities. History shows that when new knowledge gets held back economic growth suffers. Lesson: Advocate for science communication to stem the anti-science movement.

- Mokyr’s work showed that the ease and cost of accessing new knowledge is an important factor in generating economic growth. This underlines the importance of education to economic growth. He has an open mind about how important a functioning system to protect intellectual property is important for economic growth, as a patent is a significant barrier to accessing new prescriptive knowledge, at least in the short term. Lesson: Strengthen the education system and encourage use of new tools such as artificial intelligence for accessing new knowledge.

- The interplay between propositional and prescriptive knowledge is an important theme in Mokyr’s work. So, applying that idea today would mean encouraging university-industry contacts and keeping active contacts between universities and technical colleges. Lesson: Strengthen university-industry connections.

- Continue to build propositional knowledge. Mokyr showed that the knowledge base of the economy has grown significantly in the last century, and many industries are now almost 100% based on knowledge for new developments, for example, aerospace and electronics. But some sectors are less developed, notably medicine. That explains why clinical trials are needed. This trial-and-error approach is much less efficient than the scientific approach used to design a new airplane. Lesson: Continue support of university research, particularly in areas where current knowledge base is weak.

Conclusion.

The ideas developed by the 2025 Nobel prize winners can help address Canada’s growth problem. They are not rocket science, or new, and definitely not the complete answer. But they have been proven to work and implementing them will help Canada’s growth prospects.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.